Permafrost is the understructure of the Arctic, but it’s thawing at a drastic pace, putting infrastructure and landscape in peril.

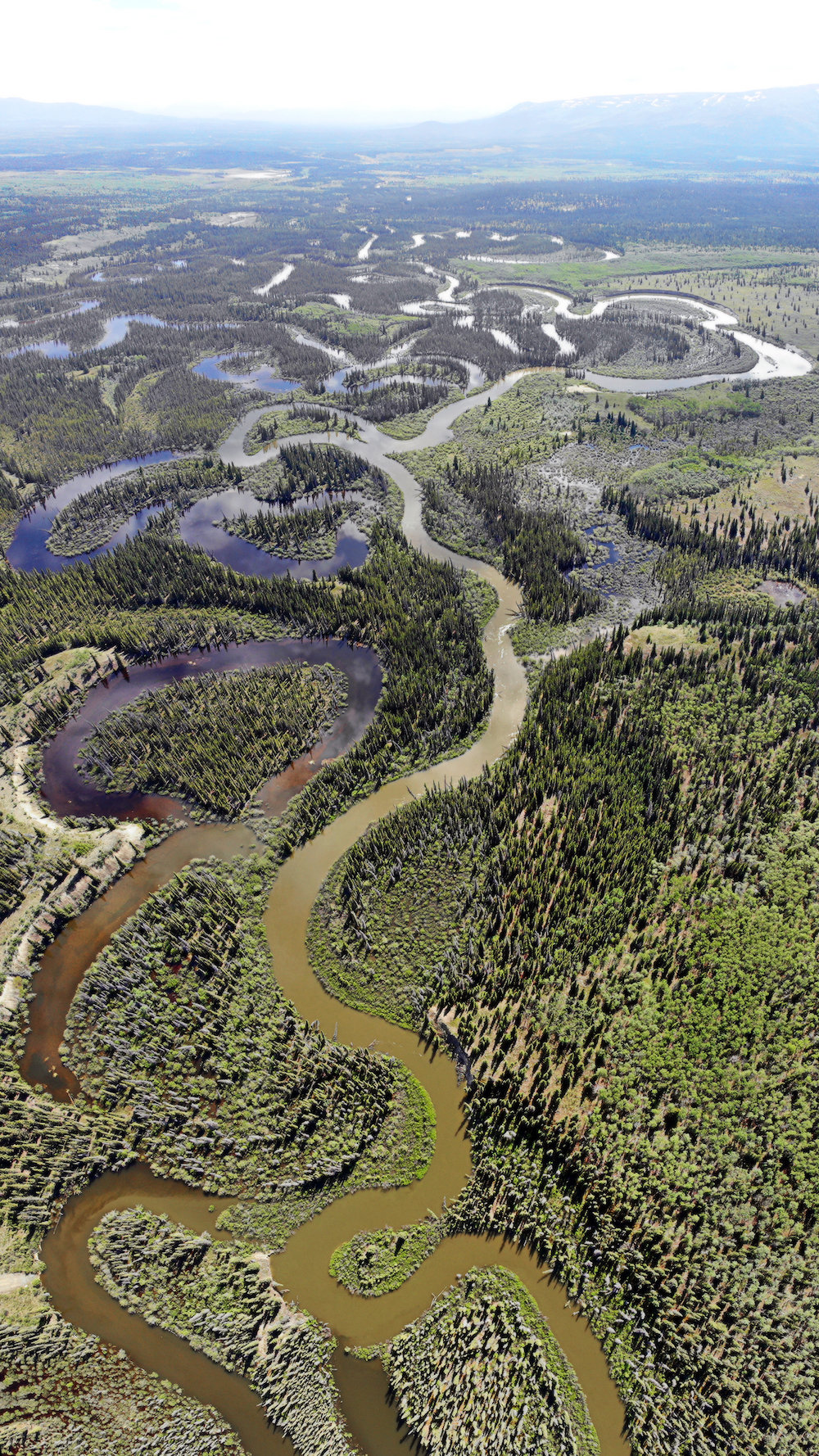

Researchers wanted to ascertain how rising temperatures and thawing permafrost are affecting the movement of the Arctic’s large rivers. A new study published in Nature Climate Change found that such rivers’ channel migration is actually decreasing. Rivers across Alaska and Canada’s Yukon and Northwest Territories migrated 20% less between 1972 and 2020, a period when the region’s temperatures spiked.

These large, meandering waterways have historically moved at a very consistent pace, but climate change has upended that predictability, said study coauthor Alessandro Ielpi, a geomorphologist at the University of British Columbia. “It’s incredibly interesting to see what happens when the river is not in a steady-state condition,” he said. “What better example and opportunity [to study this phenomenon] than looking at the response of northern rivers to climate change?”

Winding Down

Rivers naturally migrate over time because of the movement of water and sediment. Lateral migrations refer to the movement of a river’s banks as water pushes sediment from side to side. The rivers examined in this study are all in remote areas—even for the Arctic—and floodplains were a specific focus.

To measure river migrations, researchers evaluated Landsat imagery of 10 rivers that were more than 100 meters wide in Alaska, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories. These rivers, including the Yukon and Mackenzie, are in areas with varying amounts of permafrost, from continuous to sporadic.

Although researchers were originally trying to prove the generally accepted idea that the river banks would collapse without permafrost holding them in place, they were surprised to find the opposite.

The researchers compared images of the rivers’ centerlines—the approximate middle between banks—by selecting pictures every 5 years that were cloud free and taken at the same time of year. They then created a time-lapse record using dynamic time warping, an algorithm originally created for stock market predictions and now commonly used for natural systems.

They found that between 1972 and 2020, the rivers’ lateral migrations dropped by a mean rate of 3.7% each year. That number, according to the researchers, could very well be higher. Although the researchers were originally trying to prove the generally accepted idea that the river banks would collapse without permafrost holding them in place, they were surprised to find the opposite.

The findings, said Ielpi, suggest that “perhaps we need to take a step back and look at the entire natural system and understand that, yes, permafrost may contribute, but that contribution is not as strong as the contribution of, say, vegetation in shaping channel banks.”

Deep Roots

The rivers that slowed down the most were in the areas with the most increased shrubification. As the Arctic heats up, deeper-rooted shrubs like Arctic willow are sprouting, said Ielpi. The rivers with the slowest migration, he explained, are “the ones where the shrubs are advancing the most toward the channel.”

Researchers surmised that the plants’ roots hold river banks in place, restraining erosion and slowing lateral migration. They were able to link the slowdown to new plant life by using the normalized difference vegetation index to measure changes in vegetation over time.

Many Rivers to Cross

The researchers chose large rivers for the current study because they’re easier to see with older satellite imagery. With these constraints, the new findings will not necessarily translate to smaller rivers, Ielpi cautioned.

“We don’t know, as you move upland toward smaller and smaller tributaries, if the pattern will hold or not,” Ielpi said.

To find out, his team’s follow-up research focuses on smaller rivers over a shorter period time with newer images.

The idea that vegetation will stabilize river banks as thaw deepens is very interesting, said Bethany Neilson, a hydrologist at Utah State University who wasn’t involved with the study. In addition to broadening the spatial scope of the study by researching more rivers, she also sees opportunities to deepen the scope by incorporating various hydrological factors. For example, she said, violent ice breakup during spring thaws can be very destructive. “As those breakup rates change, it can really alter what gets scoured out and moved.”

The new study contributes to our understanding of how rivers at higher latitudes behave differently from those at lower latitudes, where the majority of work on river migration has been done, Ielpi said. “The study documents a change but also provides a little more information on the peculiarities of river functioning at high latitudes.”

Source: eos